Colorado’s all-star defenceman Cale Makar gets it. And let’s be honest—so do most NHL players. It’s a safe bet that most fans agree as well. But sadly, once again, NHL president Gary Bettman’s stubborn streak—the same one that denied best-on-best international hockey for years—continues to block a long-overdue fix to the league’s broken playoff format.

From The Score:

Colorado Avalanche superstar Cale Makar wants the NHL to return to its previous playoff format, and he’s adamant he isn’t alone. “I feel like all the players want back to 1 to 8,” Makar told ESPN’s Greg Wyshynski. Makar’s preference has been echoed by several players and pundits over the years, but commissioner Gary Bettman has said on numerous occasions that the league has no plans to change the playoff setup.

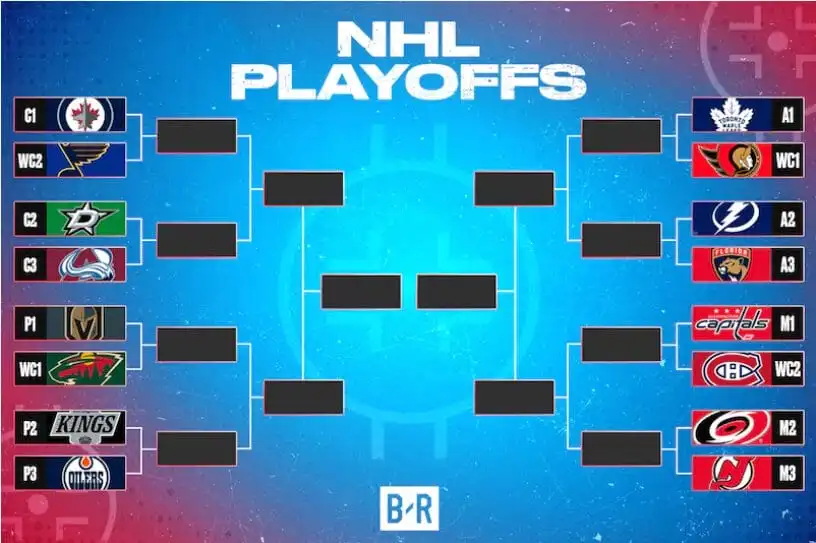

Most complaints about the format are based around repetitive matchups or Cup contenders being forced to meet in the first round because of the divisions they play in.

“I mean, if you’re from Edmonton or L.A., I’d say so, yeah,” Makar said. “Sometimes you get a good matchup and sometimes you are playing a top-six team with another top-six team like we did this past year. That’s the way she goes.”

The Oilers and Kings met in the first round for the fourth year in a row this past spring. The Avalanche, who finished fifth in the Western Conference, started the playoffs against the third-place Dallas Stars. Dallas ultimately won the series in seven games.

The “1-to-8” format Makar refers to is simple and fair: 1st plays 8th, 2nd plays 7th, and so on.

There should be a substantial reward for teams that prove, over the long 82-game grind—soon to be 84—that they’re the better team. That reward should be a smoother early path, not an ambush from another powerhouse.

Instead, fans are saddled with Bettman’s so-called “rivalry-driven” format. According to him, forcing teams in the same division to repeatedly meet in early rounds somehow preserves rivalries. In reality, it just drains the excitement and punishes success. Gary Bettman disagrees.

Really? Tell that to fans who’ve endured the same first-round clash (Edmonton vs. Los Angeles) four years running. Tell it to Atlantic Division fans who see 100-point teams wiped out before Round Two. Home-ice advantage? Sure—but one home-ice defeat and that lone reward vanishes.

Clearly, Gary Bettman has never played hockey. That might explain his blind spot for what actually fuels rivalries: emotion, not geography. Anyone who’s played—or even watched—knows that playoff hate can erupt within minutes.

This notion that only repetition breeds rivalry is absurd. When the playoffs start, every opponent is the enemy. Within a period or two, the desperation to survive takes over.

Fans hate every opponent with equal fury—not because of location or frequency, but because losing means elimination. It means “it’s all over.” It means “wait till next year.” It means roster overhauls, trades, and heartbreak. It means another summer of wondering what could’ve been.

Players feel the same. Most can’t stand losing anything—from a checkers game to a championship. For them, lifting the Stanley Cup and seeing their names etched forever is the dream. Anyone trying to end that dream instantly becomes the villain.

Even teammates clash— during practice. It happens with every team, every year, everywhere. Competition breeds friction, even when nothing tangible is at stake. Tempers flair even when friends are involved.

Returning to a traditional playoff structure won’t guarantee the two best teams meet in the Final—but it sure improves the odds compared to the current mess.

Players and fans live and die with each outcome. Every round creates its own villains, its own rivalries, its own unforgettable grudges. The hate is real.

And Gary Bettman’s playoff format? The hate is real there too. Very real.